nLab one-point compactification

.

Context

Topology

topology (point-set topology, point-free topology)

see also differential topology, algebraic topology, functional analysis and topological homotopy theory

Basic concepts

-

fiber space, space attachment

Extra stuff, structure, properties

-

Kolmogorov space, Hausdorff space, regular space, normal space

-

sequentially compact, countably compact, locally compact, sigma-compact, paracompact, countably paracompact, strongly compact

Examples

Basic statements

-

closed subspaces of compact Hausdorff spaces are equivalently compact subspaces

-

open subspaces of compact Hausdorff spaces are locally compact

-

compact spaces equivalently have converging subnet of every net

-

continuous metric space valued function on compact metric space is uniformly continuous

-

paracompact Hausdorff spaces equivalently admit subordinate partitions of unity

-

injective proper maps to locally compact spaces are equivalently the closed embeddings

-

locally compact and second-countable spaces are sigma-compact

Theorems

Analysis Theorems

Contents

Idea

The one-point compactification of a topological space is a new compact space obtained by adding a single new point “” to the original space and declaring in the complements of the original closed compact subspaces to be open.

One may think of the new point added as the “point at infinity” of the original space. A continuous function on vanishes at infinity precisely if it extends to a continuous function on and literally takes the value zero at the point “”.

This one-point compactification is also known as the Alexandroff compactification after a 1924 paper by Павел Сергеевич Александров (then transliterated ‘P.S. Aleksandroff’).

The one-point compactification is usually applied to a non-compact locally compact Hausdorff space. In the more general situation, it may not really be a compactification and hence is called the one-point extension or Alexandroff extension.

Definition

For topological spaces

Definition

(one-point extension)

Let be any topological space. Its one-point extension is the topological space

-

whose underlying set is the disjoint union of that of with a singleton set ;

-

and whose open subsets are

-

the open subsets of ;

-

the complements of the closed compact subsets .

-

(Aleksandrov 24, see Kelley 75, p. 150)

Remark

If is Hausdorff, then it is sufficient to speak of compact subsets in def. , since compact subspaces of Hausdorff spaces are closed.

Lemma

(one-point extension is well-defined)

The topology on the one-point extension in def. is indeed well defined in that the given set of subsets is indeed closed under arbitrary unions and finite intersections.

Proof

The unions and finite intersections of the open subsets inherited from are closed among themselves by the assumption that is a topological space.

It is hence sufficient to see that

-

the unions and finite intersection of the are closed among themselves,

-

the union and intersection of a subset of the form with one of the form is again of one of the two kinds.

Regarding the first statement: Under de Morgan duality

and

and so the first statement follows from the fact that finite unions of compact subspaces and arbitrary intersections of closed compact subspaces are themselves again compact (this prop.).

Regarding the second statement: That is open means that there exists a closed subset with . Now using de Morgan duality we find

-

for intersections:

Since finite unions of closed subsets are closed, this is again an open subset of ;

-

for unions:

For this to be open in we need that is again compact. This follows because subsets are closed in a closed subspace precisely if they are closed in the ambient space and because closed subsets of compact spaces are compact.

For non-commutative topological spaces (-algebras)

Dually in non-commutative topology the one-point compactification corresponds to the unitisation of C*-algebras.

Properties

Basic properties

We discuss the basic properties of the construction in def. , in particular that it always yields a compact topological space (prop. below) and the ingredients needed to see its universal property in the Hausdorff case below.

Proposition

(one-point extension is compact)

For any topological space, we have that its one-point extension (def. ) is a compact topological space.

Proof

Let be an open cover. We need to show that this has a finite subcover.

That we have a cover means that

-

there must exist such that is an open neighbourhood of the extra point. But since, by construction, the only open subsets containing that point are of the form , it follows that there is a compact closed subset with .

-

is in particular an open cover of that closed compact subset . This being compact means that there is a finite subset so that is still a cover of .

Together this implies that

is a finite subcover of the original cover.

Proposition

(one-point extension of locally compact space is Hausdorff precisely if original space is)

Let be a locally compact topological space. Then its one-point extension (def. ) is a Hausdorff topological space precisely if is.

Proof

It is clear that if is not Hausdorff then is not.

For the converse, assume that is Hausdorff.

Since as underlying sets, we only need to check that for any point, then there is an open neighbourhood and an open neighbourhood of the extra point which are disjoint.

That is locally compact implies by definition that there exists an open neighbourhood whose topological closure is a closed compact neighbourhood . Hence

is an open neighbourhood of and the two are disjoint

by construction.

Proposition

(inclusion into one-point extension is open embedding)

Let be a topological space. Then the evident inclusion function

Proof

Regarding the first point: For open and closed and compact, the preimages of the corresponding open subsets in are

which are open in .

Regarding the second point: The image of an open subset is , which is open by definition.

Regarding the third point: We need to show that is a homeomorphism. This is immediate from the definition of .

Proposition

If is a compact Hausdorff space and any point, then is homeomorphic to the one-point compactification (Def. ) of its complement subspace :

Observe also that , being an open subspace of a compact Hausdorff space, is a locally compact topological space, since open subspaces of compact Hausdorff spaces are locally compact, and of course it is Hausdorff, since is.

Proof

Since closed subspaces of compact Hausdorff spaces are equivalently compact subspaces, the open neighbourhoods of are equivalently the complements of closed, and hence compact closed, subsets in . By def. this means that the function

which is the identity on and sends (hence which is just the identity on the underlying sets) is a homeomorphism.

Universal property

As a pointed locally compact Hausdorff space, the one-point compactification of may be described by a universal property:

For every pointed locally compact Hausdorff space and every continuous map such that the pre-image is compact for all closed sets not containing , there is a unique basepoint-preserving continuous map that extends .

To see this, note that such a map is necessarily unique. It suffices to show existence. Extend to a map such that . If is open, and then is open. If then is closed and is compact, by the hypothesis. Put ; then is closed and compact and so is open. It follows that is continuous.

This property characterizes in an essentially unique manner.

is dense in precisely if is not already compact. Note that is technically a compactification of only in this case.

is Hausdorff (hence a compactum) if and only if is already both Hausdorff and locally compact (see prop. ).

Monoidal functoriality

Proposition

The operation of one-point compactification (Def. ) does not extend to a functor on the whole category of topological spaces. But it does extend to a functor on locally compact Hausdorff spaces with proper maps between them.

(e.g. Cutler 20, Prop. 1.6)

Proposition

(one-point compactification intertwines Cartesian product with smash product)

On the subcategory in Top of locally compact Hausdorff spaces with proper maps between them, the functor of one-point compactification (Prop. )

-

sends coproducts, hence disjoint union topological spaces, to wedge sums of pointed topological spaces;

-

sends Cartesian products, hence product topological spaces, to smash products of pointed topological spaces;

hence constitutes a strong monoidal functor for both monoidal structures of these distributive monoidal categories in that there are natural homeomorphisms

and

This is briefly mentioned in Bredon 93, p. 199. The argument is spelled out in: MO:a/1645794, Cutler 20, Prop. 1.6.

Examples

General

Example

If is already itself compact, then its one-point extension in the sense of Def. is the disjoint union of with a singleton .

Namely, in this case the open neighbourhood of consists of just itself, which is hence an open point. But it is also a closed point, being the complement of .

Compactification of discrete spaces

Example

(one-point compactification of countable discrete space)

Consider the natural numbers regarded as a discrete space. This is not compact. Its one-point compactification has as underlying set the disjoint union of the natural numbers with an element “at infinity”, and its open subsets are those subsets that either do not contain , or which contain and are cofinite subsets.

This space is actually a Stone space, and corresponds via Stone duality to the Boolean algebra of the finite and cofinite subsets of , with the usual Boolean algebra operations of union and set-complement.

To see this, notice that the clopen sets in the space are those that are either finite and not containing , or cofinite and containing . So a clopen set is determined by giving either a finite or a cofinite subset of , and then adding if it is cofinite. Under this correspondence, the Boolean algebra operations on finite and cofinite subsets of correspond to the Boolean algebra operations on the clopen sets.

Another reason that this space is important is because to give a continuous map to a topological space is to give a convergent sequence in . This can then be used as a foundation: Johnstone's topological topos is a category of sheaves on the continuous endofunctions of , and subsequential spaces are a subcategory of concrete sheaves.

Euclidean spaces compactify to Spheres

We discuss how the one-point compactification of Euclidean space of dimension is the n-sphere.

Example

(one-point compactification of Euclidean n-space is the n-sphere)

For the n-sphere with its standard topology (e.g. as a subspace of the Euclidean space with its metric topology) is homeomorphic to the one-point compactification (def. ) of the Euclidean space

Proof

Pick a point . By stereographic projection we have a homeomorphism

With this it only remains to see that for an open neighbourhood of in then the complement is compact closed, and conversely that the complement of every compact closed subset of is an open neighbourhood of .

Observe that under stereographic projection the open subspaces are identified precisely with the closed and bounded subsets of . (Closure is immediate, boundedness follows because an open neighbourhood of needs to contain an open ball around in the other stereographic projection, which under change of chart gives a bounded subset. )

By the Heine-Borel theorem the closed and bounded subsets of are precisely the compact, and hence the compact closed, subsets of .

Remark

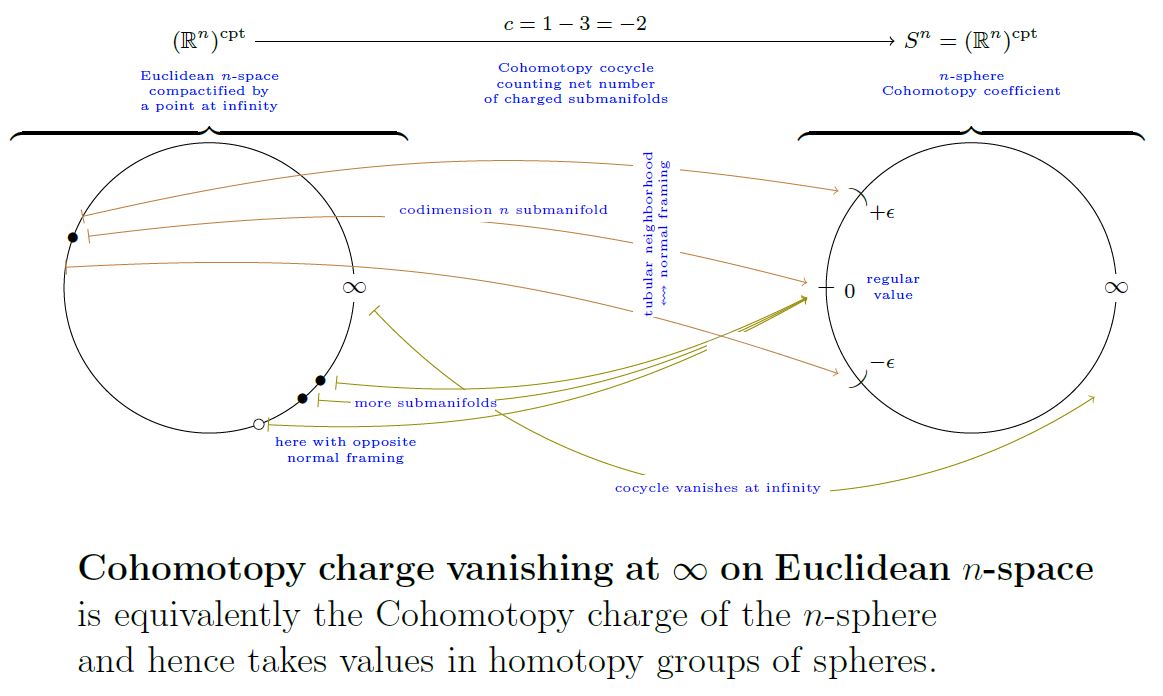

(relevance for monopoles and instantons in gauge theory)

In physics, Example governs the phenomenon of monopoles and instantons for gauge theory on Minkowski spacetime or Euclidean space: While such spaces themselves are not compact, the consistency condition that any field configuration carries a finite energy requires that gauge fields vanish at infinity.

This means that if is the classifying space for the corresponding gauge field – e.g. for Yang-Mills theory with gauge group – and if denotes the base point witnessing vanishing fields, then a field configuration/cocycle

on in -cohomology vanishes at infinity if outside any compact subset its value is the vanishing field configuration .

But by Def. this is equivalent to the cocycle extends to the one-point compactification as a morphism of pointed topological space:

The following graphics illustrates this for an n-sphere itself, hence for charges in Cohomotopy cohomology theory:

graphics grabbed from SS 19

For more see at Yang-Mills instanton – SU(2)-instantons from the correct maths to the traditional physics story.

Linear representations compactify to representation spheres

Via the presentation of example , the canonical action of the orthogonal group on induces an action of on , which preserves the basepoint (the “point at infinity”).

This construction presents the J-homomorphism in stable homotopy theory and is encoded for instance in the definition of orthogonal spectra.

Slightly more generally, for any real vector space of dimension one has . In this context and in view of the previous case, one usually writes

for the -sphere obtained as the one-point compactification of the vector space .

As a special case of Prop. we have:

Proposition

For two real vector spaces, there is a natural homeomorphism

between the smash product of their one-point compactifications and the one-point compactification of the direct sum.

Remark

In particular, it follows directly from this that the suspension of the -sphere is the -sphere, up to homeomorphism:

Thom spaces

For a compact topological space and a vector bundle, then the (homotopy type of the) one-point compactification of the total space is the Thom space of , equivalent to .

For a simple example: the real projective plane is the one-point compactification of the ‘open’ Möbius strip, as line bundle over . This is a special case of the more general observation that is the Thom space of the tautological line bundle over .

Locally compact Hausdorff spaces

Example

(every locally compact Hausdorff space is an open subspace of a compact Hausdorff space)

Every locally compact Hausdorff space is homeomorphic to a open topological subspace of a compact topological space.

Proof

In one direction the statement is that open subspaces of compact Hausdorff spaces are locally compact (see there for the proof). What we need to show is that every locally compact Hausdorff spaces arises this way.

So let be a locally compact Hausdorff space. By prop. and prop. its one-point extension (def. ) is a compact Hausdorff space. By prop. the canonical inclusion is an open embedding of topological spaces.

Related concepts

References

The concept goes back to

- Pavel Aleksandrov, Über die Metrisation der im Kleinen kompakten topologischen Räume, Mathematische Annalen (1924) Volume: 92, page 294-301 (dml:159072)

Textbook accounts:

-

John Kelley, p. 150 of: General topology, D. van Nostrand, New York (1955), reprinted as: Graduate Texts in Mathematics, Springer (1975) [ISBN:978-0-387-90125-1]

-

Glen Bredon, p. 199 of: Topology and Geometry, Graduate Texts in Mathematics 139, Springer 1993 (doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-6848-0, pdf)

Review:

- Tyrone Cutler, The category of pointed topological spaces (2020) [pdf, pdf]

See also

- Wikipedia, Alexandroff extension

Last revised on February 14, 2024 at 02:23:02. See the history of this page for a list of all contributions to it.